In an unassuming courtyard on Zoloti Vorota, a clay dog figure sits guard. It watches over the steps leading to a warm and surprisingly cozy basement, where our heroine, Viktoria, works. The workshop door is wide open. At first, you’re surprised—it’s a cold November outside. But then you understand why. The kilns for firing ceramics heat up to over 1000 degrees. On the couch near the workshop entrance, there’s a white-and-red dog, not clay but real.

Read also: Protection of civilians in Ukraine: a detailed overview of the UN report for October

Lion hunters

“This is Obi,” says the owner. “An African basenji. Their closest relatives are wolves and dingoes. They’re five thousand years old. And they used to hunt lions.” Tall, slender, and red-haired, Viktoria welcomes us. Obi greets us with a friendly gaze and immediately rolls onto his back. “Ignore the genes of the stern lion hunters,” he seems to say. “I can’t cover the kilns for the photo, sorry about that,” Viktoria smiles. There are two kilns in the workshop. “This bigger one,” she says, “is local. I rented the workshop with it already. And this small one (pointing to a metal cylindrical kiln, resembling a cauldron), is mine. I brought it from Kharkiv. And this is the main computer for these kilns. It shows the temperature.” The gauge reads 720 degrees. The kiln is cooling down, Viktoria explains. It can be opened at 150 degrees. Otherwise, the pieces will shatter.

“Sometimes people ask me why I can’t make a piece quickly. First of all, any idea needs to be processed, thought out, and figured out how to best implement it. Secondly, some processes I physically can’t speed up. For example, cooling down the kiln. So you sit and wait. Sometimes you go a bit wild after weeks spent alone in the workshop (smiles).”

A saucer with a golden “kaiomochka”

I’m from a small town in the Luhansk region. One of my brightest memories about ceramics from childhood is my grandmother’s plate with an Olympic bear, from which I was forced to finish everything. That golden “kaiomochka” still makes me roll my eyes. My grandmother used to say to me, “Eat up, and you’ll see the bear.” Unsurprisingly, I didn’t like the plate with the bear.

These motifs later became the basis for my “Childhood” collection of dishes. When I started working with ceramics, I decided I would create something that didn’t exist. I wasn’t interested in becoming an Epicenter.

In my small homeland, there was a utilitarian approach to clothing and household items. But for some reason, my mother had a penchant for aesthetics. She loved to dress differently from others. By the way, I studied already during independent Ukraine, but we had a school uniform with blue pinafores and Soviet aprons.

“I’ll definitely come back for this cup”

This fall, chaplains involved me in the “Circle of Pokrova” project. They heard about the effect of clay, about the work of the fingers, how it affects emotional state. They thought that the military needed such emotional relief. Together with the chaplains, I went to Donetsk region, to the positions of the 152nd and 93rd brigades.

I held workshops for the military, who had either just returned from a combat mission or were about to go on one. I remember one guy (one of those who was going on a combat mission) said: “Well, I’ll definitely come back for this cup.” Then many soldiers wrote to me in private messages, thanking me.

Men’s tantrums

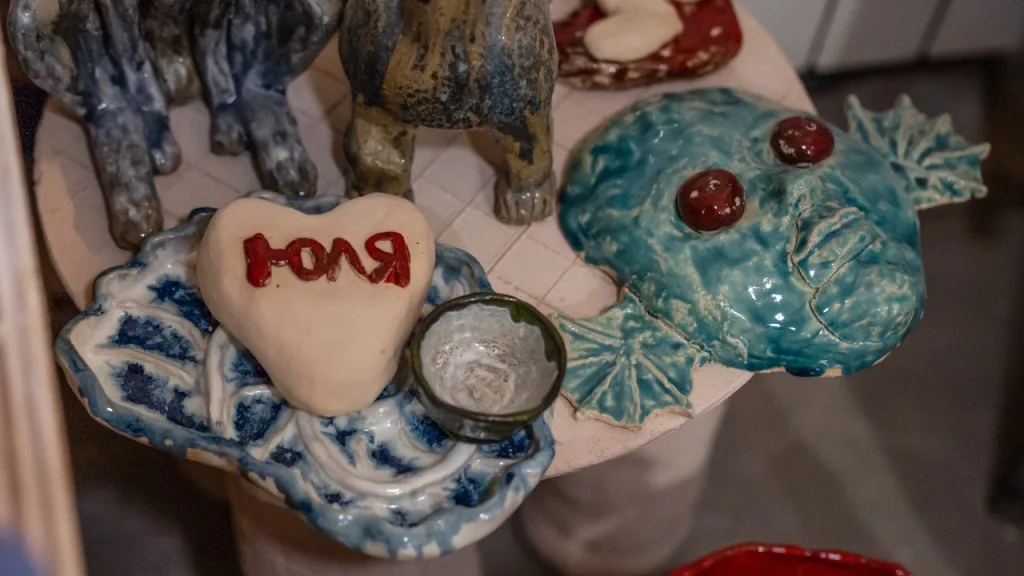

This heart, “Yulia,” was made by a soldier near Pokrovsk, from the 152nd brigade. Dedicated to his wife. These works are from the 93rd brigade. The red poppy. This is again the 152nd. A swan. Such symbolic images.

It’s interesting that guys have a harder time when something doesn’t work out for them. In my commercial classes, sometimes they would just turn around and leave. One guy even had a tantrum. So I always worry about the skeptical reaction of men. But the military took the offer to mold very well. There were those who stood and stood, looked and looked: “No, no, this is not for me.” And then at the last moment: “Okay, I’ll quickly make a cup and that’s it.” And they molded something cool.

Here someone molded themselves, probably. Such a totemic figure. Here’s a cross, this was molded by the chaplain. I was very afraid that it would crack, because ceramics can crack, sometimes it bursts. I thought, God, let this cross remain intact, so that the chaplain doesn’t think it’s some kind of evil spirit (laughs).

Read also: “Fashion space for all”: adaptive clothing as a way to inclusivity in Ukraine

Plates from the “graveyard”

I first saw plates for people with amputations on the Amazon website. I thought it was an American development. But The Village journalists dug a little deeper. It turned out that they were invented and implemented in Germany after World War II. I was interested in these plates, I saved them in my “graveyard” (that’s what I call a place where saved links are stored, which I usually don’t get around to).

The pegs on these plates serve to secure food. People who eat on flat plates and use only one working hand usually have a problem with food “escaping.” And in these plates, one edge is higher, and the other is lower, on the contrary, to prevent this.

For example, one soldier wrote that it was his favorite plate for eating boiled vegetables. It’s also convenient for cutting bread or croissants. I tested it myself.

I first made these plates for the Naushi establishment. Once I came to them with my plate to eat ramen. They were interested in the fact that I was a ceramicist. Then they found out about inclusive plates and wrote to me. I changed the plate from Amazon a little. For this, I consulted with ergotherapists and my friend who has small children. After that, the first small batch was made.

Then I made a few plates for the military to try. I thought there would be more negative feedback and requests to change something. But so far there haven’t been any. Maybe people are shy, or maybe the plates are really good (smiles). Over time, other establishments and hospitals started contacting me. Even representatives of the Ministry of Health wrote.

You can live without it, but…

Some people wrote to me: “I can do without your plates.” True, you can do without it. It doesn’t solve global problems. But it makes life a little simpler and brighter. Imagine a person with an amputation using a plastic plate from OLX. And when the family sits down at the table, everyone has beautiful ceramic plates, and he has a plastic one, like a child. It’s depressing.

Another deep problem is that people who use only one hand are shy about eating in establishments. If at home they can somehow adapt, then in public it is psychologically more difficult. I am very glad that among my customers there are catering establishments in Kyiv. This is an important step towards accessibility.

One inclusive plate costs 700 hryvnia. I have an option of suspended plates. Anyone can pay for them, and the military in hospitals will use them.

The worst thank you from the Ministry of Health

One employee of the Ministry of Health wrote to me: “Thank you for your sacrifice.” It was the worst thank you in my life (laughs)!

I have a philosophical attitude to my work. Today this plate is needed by someone, tomorrow it will be needed by me. I try to treat people the way I want them to treat me. It seems to me that this is a good functioning of the world. As long as I have the opportunity to sit in Kyiv, rent a cool workshop on Zoloti Vorota, and realize my ideas, then a plate for a soldier is the minimum gratitude that I can do.

***

“This, by the way, is Slavsk shamotte,” Viktoria says, holding up a heavy clay plate with an octopus. “Unfortunately, there will be no more of this clay. The quarry where it was mined is now occupied. And this white faience was mined in the city of Chasiv Yar. There will be no more of that either.”

Viktoria sorts through the ceramic pieces, examining them, showing the texture of the clay, talking about the specifics of mining and purifying the raw materials, and baking the finished product in the kiln.

“When you go east from time to time, you see how everything is gradually dying. They start building defensive lines where they weren’t a week ago. They scrutinize civilians more closely at checkpoints. There are fewer people on the streets. Enemy drones are flying… And it’s happening very fast.”

Read also: Anna Kuzmenko: “Previously, a bone marrow transplant in Ukraine was just a dream. Now it’s a reality”