Maria is originally from Crimea. After the occupation in 2014, she moved to Kyiv at the age of 18 and graduated from the Faculty of History at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. Since 2023, she has been the head of the Almenda Centre for Civic Education, which works to protect the rights of children and young people from the occupied territories, including reintegration.

“Since my teenage years, I have been impressed by educational work. After the occupation of Crimea, I started working on the topic of Russia’s war crimes, dealing with Crimean cases at the Ukrainian Helsinki Union. At some point, I completely returned to Almenda. My mother is one of its co-founders. So it is not surprising that I grew up with this organisation. It was founded when I was still at school, and many processes took place at our home. My mother was a history teacher and at the time of the occupation she was a member of the admission committee, so she stayed in Crimea until the very end to graduate students with Ukrainian diplomas. It was one of her former students, who had worked for the SBU and moved to the FSB after the occupation, who warned her about the case against her. One of her colleagues wrote a denunciation against her. After that, my mother had to leave quickly.”

Read also: Platform ‘Towards’. How veterans can find a job

‘Russia’s actions in the occupied territories are not just a violation of rights, but a crime against humanity’

— What is the history of the Almenda NGO and what does the organisation do today?

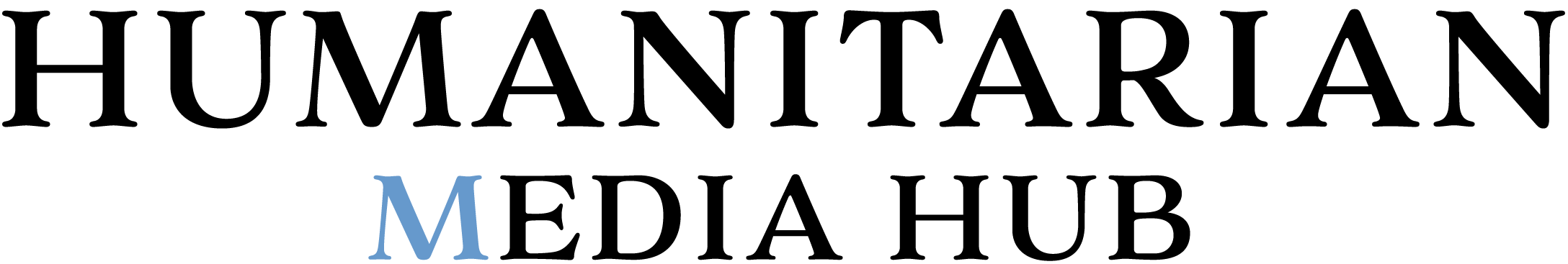

— The Almenda NGO was founded in 2011. Initially, its goal was to build civil society in Crimea. I think we succeeded, because the organisers of the protests in Crimea were participants in our projects. After the occupation, the focus changed. Now our mission is to facilitate the reintegration of the (de)occupied territories, primarily through children.

Our key focus is access to Ukrainian education, both secondary and higher, for children in the occupied territories. At the national level, distance education is not adapted to their needs. We help them to enter Ukrainian universities, accompany them, and lobby for changes in legislation, because these children do not have Ukrainian documents, have not studied Ukrainian, and many simply do not have the means to move.

Another important aspect is working with Ukrainian society to prevent stigmatisation of children leaving the TOT. It is important to explain to their peers what is happening in the occupied territories and who is really to blame.

The third area is the restoration of justice. We document crimes, cooperate with law enforcement agencies and international organisations. Our strategic goal is to prove that Russia’s actions against children in the occupied territories are not just human rights violations, but a crime against humanity.

‘Children are taught that defending Russia is a “sacred duty”’

— What is Russia doing with children in the occupied territories?

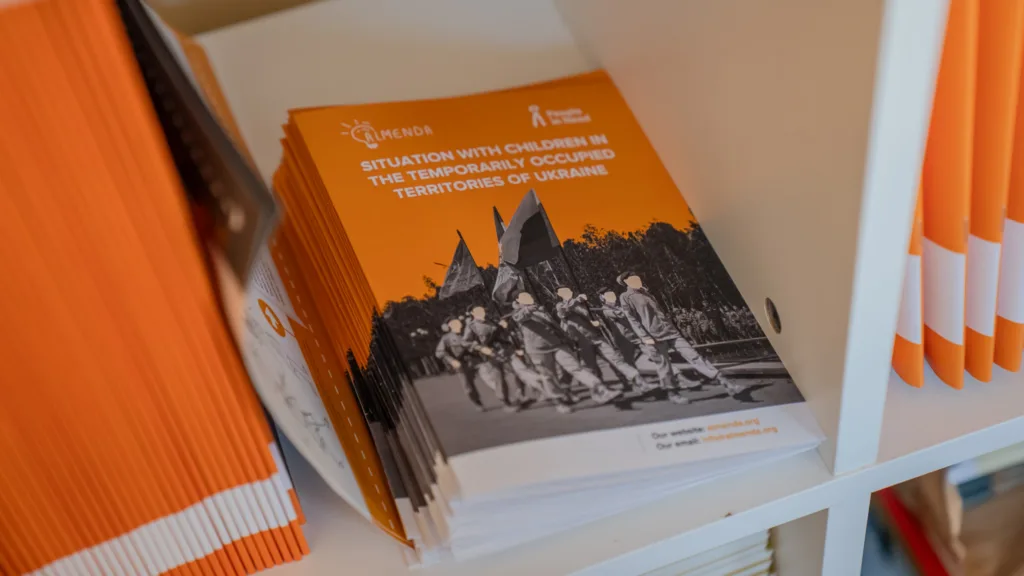

— Russia has created a comprehensive system of destroying Ukrainian identity. It consists of several components.

First of all, it is the exclusion of everything Ukrainian from education and culture. It includes teaching according to Russian standards, confiscation of Ukrainian books, and the installation of monuments and symbols of occupation. Most schools have already unveiled memorial plaques dedicated to the so-called war heroes, or, as they say, the so-called ‘Svoboda’. The painful thing is that some of the people on these plaques are former students of these schools who were victims of indoctrination, militarisation and forced conscription into the armed forces of the occupying country.

The second is militarisation. Cadet classes, meetings with the Russian military, ideological education, youth movements. Children are taught that their ‘sacred duty’ is to defend Russia. They are growing up in a world where Ukraine does not exist, and any pro-Ukrainian manifestations are subject to persecution. For example, psychologists may be forced to work with a child. And from the age of 14, pro-Ukrainian actions can be considered extremism and prosecuted.

Another aspect is forced displacement and deportation. When we talk about deported children, most of them are children from institutional settings. But children with parents can be forcibly displaced. This happens in different ways. Sometimes children are sent to ‘rest camps’, after which they are transferred to the Russian Federation, and their parents are not allowed to pick them up. These children are further cut off from their community and subjected to increased Russification.

No one knows the exact number of deported children. According to the data available to Ukraine, it is 19,546 children, but the real figure could be much higher.

‘In the human rights sphere, you need to be able to play the long game’

— How has the organisation’s work changed since 2022?

— Before the full-scale invasion, we focused only on Crimea. When Russia occupied Crimea, it immediately began to integrate it into its space, and in the eastern regions, at first, there was a game of independent republics. After the full-scale invasion, it became obvious that Russia was using the Crimean scenario in the occupied regions. That is why we have expanded our activities to the south and partly to the east of Ukraine.

— What organisations do you cooperate with?

— We cooperate with international partners: Civil Rights Defenders, the Netherlands Helsinki Committee, Human Rights House Foundation, Open Society Foundations. We also work in coalitions in Ukraine, such as the Ukraine 5 am coalition, the Crimean Human Rights House NGO, and with individual human rights organisations, such as the Regional Human Rights Centre, Vostok SOS, Donbas SOS, Group of Influence, Crimea SOS, Zmina, and others

— What qualities should a person have to work in this field?

— First of all, a thirst for justice. In human rights work, you rarely see quick results, you need to be able to play the long game. Professional skills can be developed, but without internal conviction, there will be no motivation.

‘We work so that children in the occupation have a chance for the future’

— What helps you not to burn out?

— I used to believe that I would be able to show my child the house where I grew up. Now I’m not sure that this will ever happen. But I am very much supported by the stories of the people we have helped. For example, I accidentally met a man in Lviv who told me that he knew our organisation and that he was a winner of one of our projects in 2016. Or my mother accidentally met a person in a gallery whose child was helped by our organisation to enter university. Such stories show that we are moving in the right direction. For some people, this is a valuable opportunity to change their lives and not become cannon fodder. Because this is what Russia really wants to do with our children under occupation.

— What are Almenda’s plans for the future?

— Our goal is for children under occupation to have a chance for the future. And also for Ukrainian society to continue to consider the temporarily occupied territories as its own and the people who live there as its fellow citizens. We must not only restore the borders, but also preserve social unity.

— What book would you recommend?

— Harry Potter. For me, this book is about how no matter how hard it is, there will still be something bright at the end.

— What do you do when something terrible happens, like the attack on Okhmatdyt?

— Roll call between relatives. But when the full-scale invasion started, my husband and I just packed our backpacks and went to the military enlistment office. Spoiler alert – we were not accepted (laughs).

— If it wasn’t for the war, I would never have known…

— …how painful it is to lose your home.

Read also: Ukraine is on the verge of a food crisis. How the war affects access to food